As mentioned in a prior post, Gregory of Nazianzus spawned a significant scholarly tradition. His works accumulated scholia from an early date, and several different commentaries have come down to us for several of his works.

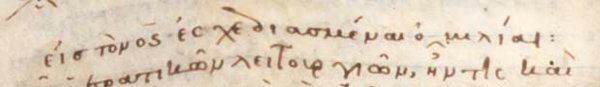

In this post, I translate Nicetas of Serrone’s on Or. 41:15. To my knowledge, the Greek text of commentary has not been published in its entirety. I have transcribed the Greek text from CMB Codex Graecus 140 folio 94 and following. This codex preserves a selection of Gregory’s homilies in their entirety, along with Nicetas’ commentary. The images of the manuscript are freely available online.

For convenience, I copy in my translation of Gregory from the prior post. In that post, I translate 41.15-16, but here I only deal with 15. For my transcription of the Greek text (of both Gregory and Nicetas), see here. Here’s the English.

Gregory of Nazianzus. Or. 41.15

[15] They were thus speaking in foreign languages, and not their own, and this was a great miracle: the message was being proclaimed by those who had not been instructed. This was sign to the unbelievers, not to the believers, so that it might be a sign of judgment against the unbelievers, for it is written, “’in different languages and in strange lips I will speak to this people, and thus they will not hear me,’ says the Lord.”

But, “they were hearing.” But wait here for a bit, and let us raise the question about how to divide this sentence. The reading has an ambiguity, which arises because of punctuation. Were they each hearing their own language, which implies that once voice was resounding through the air, but that many were heard? Thus, as it was traveling through the air, so that I may speak more clearly, one language [1] became many.

Or, should we place a pause after “they were hearing,” and thus join “as they were speaking in their own languages” with what follows. Thus, those “who were speaking,” were speaking the languages of the audience, so that we might understand it as, “foreign languages.” [1] I much prefer this approach [2]. In the former case, the miracle would belong more to the hearers than to the speakers. But in the latter, the miracle belongs to the speakers, who even as they were being accused of drunkenness were clearly working wonders by the Spirit through their voices.

[0] See 1 Cor 14:20ff

[1] Several times in the passage, Gregory uses φωνή to mean language. This word generally means “sound” or “voice” but “language” is a possibility according to LSJ. Gregory is also likely pulling from Neoplatonic discussion of φωνή.

[2] There is some doubt about this phrase. Rufinus’ early Latin translation appears to be confused about Gregory’s preference on the matter, and it may be that his base text lacked this sentence. We have some fairly early Syriac translations (c. 700-800) that have the line (thanks to Charles Sullivan for untangling the Syriac).

Nicatas of Serrone. Commentary on Or. 41.15

For it is written in the book of Acts about the apostles, that “they began to speak in different languages.” That is, the languages of the listeners, and not their own. For the languages of the hearers were not native to the apostles. This was a most marvelous occurrence, because the apostles were speaking a language that they had not learned. Just as the divine apostle says when writing to the Corinthians, these languages were a sign, not to the believers, but to the unbelievers, so that there may be a sign of judgment for them, and that when they saw this, that did not believe, as it is written, “in foreign tongues I will speak,” and the rest. Now where is this written? Chrysostom says that it is in Isaiah, but it is not found there, unless it was removed maliciously or was overlooked by mistake.

This is from the book of Acts, that “each one was hearing in their own language as they were speaking.” But the Theologian2 raises a difficulty. Presently, it is necessary to identify and resolve the ambiguity that is found there, that is, to punctuate it and solve the problem. He has presented two resolutions, so that he may establish the second. “Were the apostles,” he asks, “speaking one and the same language, while their voices became many as they resounded through the air? In which case, each of the hearers understood their own language. Or, shall we punctuate after “they were hearing?” Then, we would join “as they were speaking,” to what follows, so that the sense would be that the nations were hearing as the apostles were speaking their own languages, that is, in languages foreign to the speakers. This indeed fits much better, for he says that if the apostles were speaking in only one language, while the audience divided it into their own, then the miracle would belong to the audience. But if you punctuate after “they were hearing,” then you may infer that the apostles were speaking in the languages of the audience, and that the miracle belongs to the apostles. After all, it is clear that, even as they were being accused of drunkenness, that they themselves were speaking in the languages of the audience through the Spirit. Everyone who heard his own language was burning in his heart, since he saw that the apostles were not only speaking to him, but also speaking the message to those of other languages. The one who accuses them of a debauched frenzy seems not to understand the foreign languages the apostles were speaking.

As always, suggestions and corrections are welcome.

ἐν αὐτῷ,

ΜΑΘΠ